|

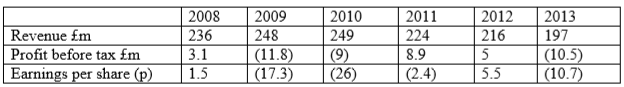

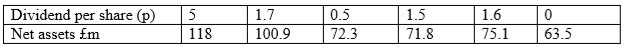

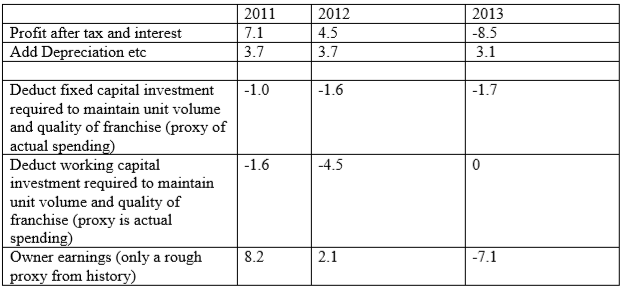

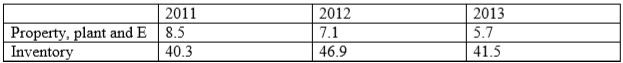

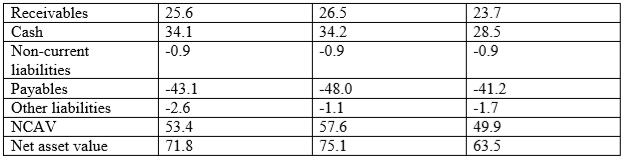

French Connection’s (FC) profit record is appalling. The only reason for looking at it is because it has net current assets much larger than market capitalisation and there are some reasons to believe that the assets will not be run down before profitability is restored. The fact that I put the probability of a return to health at less than 50% does not fatally wound the case for investment because if a turnaround is achieved the pay off will be 3-fold, 4-fold, 5-fold or more. An investment prospect with a less than 50% chance of success has to be taken only as part of a diversified portfolio, where, even if 60% of firms are failures, the few successes result in a satisfactory outcome. There are many negatives to weigh against the positives. I would be interested to hear how you weigh them. Investment category French Connection may fall into Benjamin Graham’s Net Current Asset Value style of value investing. This is: Shares that sell for less than the company’s net working capital alone. That is, the value of the current assets after deducting all liabilities, both current and long-term. Graham did take note of the possible market rationalisations justifying why companies sell for less than the value of their net working capital but frequently found them inadequate. In reality the negative factors were not of sufficient detriment to the financial strength of the company to justify pushing the share price so low – at least this was the case for the majority of shares within a portfolio of shares of this kind. He took current assets without placing any value on fixed assets, intangibles or goodwill, deducted all liabilities, and divided this by the number of shares, thereby giving a net current asset value (NCAV) per share. If this was more than the actual share price, then the company’s share was undervalued and therefore was a serious contender for investment. However, there is another stage of analysis: once a company passes muster on its quantitative elements, its qualitative elements are addressed, and an investor will then feel ready to invest. When a share selling for less than its NCAV is found the analyst should then check that its earnings are stable, its prospects are good given its strategic position and it has a good team of managers. At times of market downturns share buyers become fearful that there is worse to come; that a high proportion of quoted companies will fail to survive, waste resources in their struggle and then die, leaving the shareholders with nothing. This is exactly what happens to dozens of corporations. Graham accepted this but believed that a sufficient proportion of the shunned companies will regain value, so that buying a portfolio would be worthwhile. He believed that market pessimism can be indiscriminate. In the rush for the exit people dump shares for which there are good grounds for believing that recovery will eventually occur, as well as the real dogs. His reasons for expecting a revival of most of these companies: 1. Industries recover from downturns; in an overcrowded, over-supplied industry with low prices some companies do go under, leaving the survivors with a greater share of an improved market and higher profits. 2. Management can change their policies or be replaced, enabling their company to pursue a more profitable route. Managers in many of these poorly performing companies wake up and realise that they have to do better – after all their livelihoods are under threat. They switch to more efficient methods of production, introduce new products, abandon unprofitable lines. Sometimes shareholders need to apply pressure and force them to take a more commercial strategy focused on shareholder returns. The shareholders may replace the current team to do this. 3. Companies may be sold or taken over and their assets better used. 4. The management of a company selling below liquidation value must provide a frank justification to the shareholders for continuing. If a company is not worth more as a going concern then it is the shareholders’ interest to liquidate it. If it is worth more than its liquidating value then this should be communicated to the market. ............This qualitative analysis focuses on the following: Competitive position of the firm within its industry The operating characteristics of the company The character of management The outlook for the firm The outlook for the industry (from Great Investors (2011) FT Prentice Hall) See Testing Benjamin Graham’s Net Current Asset Value Strategy In London (2008) for a statistical analysis of the performance of investing in a portfolio of NCAV shares. Some data Share price: 30p Market capitalisation: £30m NCAV (as reported): £49.9m Revenue: -Approx. 70% UK/Europe (141 shops, 71 stores in UK and 46 concessions in UK and Europe). Operating profit: Retail lost £16m. Wholesale made £3.9m -25% N. America (17 shops) Op. Profit: Retail lost -£1.6m. Wholesale made £7.8m -Rest of world: wholesale made £0.5m op profit -Other income: UK £6.8m, NA £0.7m, RoW £1.6m Reasons for doubt In most NCAV firms you will find several reasons to want to hold your nose. Let’s look at those negatives for FC first: 1. Record No value generated for shareholders for a very long time. A story of decline. There are some businesses where management do not have to be smart every day because the franchise can carry them through years of poor management, (e.g. Coca Cola, Disney, Diageo). In retail you need to be smart every day because there is always a competitor with great innovation and flair snapping at your heels – especially in fashion retailing. An owner earnings analysis does not make for comforting reading either: 2. Comments from many sources that they still have not yet got the pricing and store display right in the UK/Europe stores, even if there may be a glimmer of light on the styling. 3. Comments, unconfirmed, that the dominant shareholder (42%), founder, chairman and CEO is domineering and inflexible 4. Lease obligations amounting to over £200m, but spread out over many years. Should they be included in liabilities? (if so, how do we account for the assets these obligations provide?) 5. Even the Board are not anticipating a quick turnaround; aiming for breakeven in the year ending 31.1.15. 6. The brand is old and faded. Some positives 1. Cash at year end 31 January 2013: £34m, with no bank debt. January is a very advantageous point in the year to report net cash. However, even at the worst point net cash was reported as £10.6m during the year. Even better: in May 2013 it reported cash of £15.7m compared with £10.4m the previous year. Also no pension deficit. 2. NCAV Bear in mind that Graham insisted that we reduce the reported receivables by one-fifth and the inventory by one-third of their reported value. Even with these deductions NCAV is significantly greater than market capitalisation. The question are: (a) Whether inventory is really worth what the company says it is? (b) Whether cash will be squandered?

2. While UK/Europe retail is doing very badly, the licensing and wholesale business continues to thrive (with a few bumps). Licensing alone can generate £5-£9m with few capital requirements 3. All it takes for the turnaround is good design. New head of design in May 2013 New head of Retail in Sept 2012. New head of production in October 2012 New head of multichannel October 2012 4. Asian growth: An aspirational brand in Asia, especially in China and India where operations are profitable and growing (opening 4 new stores in China this year and 10 in India). 5. Store leases in UK/Europe are likely to be for 15 years. This means that on average they have 7-8 years to run. Therefore over the next few years, store by store they can (a) stem losses by selectively not renewing leases (b) get rent reductions in a hard hit store rental market. The cash available combined with further reductions in working capital requirement releasing more cash, will see them through the next few years. Disposals in 2012/13: 2 stores in UK/Europe, 3 in N America. In process of closing one store and 6 concessions. Likely to close two more this year. About 10% of leases up for renegotiation each year 6. e-commerce is rising in importance, now 10% of sales 7. Sell in 30 countries with 1,000 stockists. Skilled weeding out of unprofitable activities still leaves much to build upon. 8. Branded sales (wholesale and licences for glasses etc.) of £400m, on which royalties are paid. Brand is still powerful in some segments/geographies 9. Trading revenue is now generally flat rather than falling, but such green shoots could wither. 10. Founder determination not to be seen as a failure in the retail game Some further thoughts A contribution to a bulletin board (ADVFN) posted 25.7.13 I have been reading the intelligent debate between PaulyPilot and CR with great interest. Thank you for bringing such thoughtfulness and expertise to the table. I have an idea that I think may help. As you’ll see I agree with both of you!! First let me start with an analogy: You go to the racecourse with two friends. One friend says that the positive points about a particular horse outweigh the negative the other says that the negative outweigh the positive. After listening to the debate you think that the chances of the horse being a winner are only 40%. Should you place a bet? Rationally that depends on the odds you are being offered. If you can get 5 to 1 odds then, even though the pessimistic person is more likely to be right, if you bet on many horses like this then over a period of time you will come out fine. Paul, with a great deal of industry knowledge, says that if the management do get their act together then this can be a multibagger. I agree, but that is a big ‘if’. If I do buy now, then in three years the chances (say 60%) are that I will look back and say that the company fell at a fence and I lost my money. Does that make it a bad investment decision? No. Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett tell us that investment is not about getting every decision right in the sense that every one turns out a winner. You must factor in the odds as well. Thus if you purchase 10 shares in this category of Graham’s Net Current Asset Value shares over a period of years you will come out fine. You might like to see the evidence for such an assertion. As well as Benjamin Graham’s record you might like to look at an academic paper I wrote with Xiao Ying for The Journal of Investing ‘Testing Benjamin Graham’s Net Current Asset Value Strategy In London’ (2008). Being a statistical piece of work we were unable to filter out plain no-hopers or those with hidden liabilities (e.g. today we have Aga with its massive pension liabilities or Mallett with its shareholder wealth consuming managers and ‘value’ tied up in hard to value antiques) and yet, even with that constraint, the overall portfolio performance was very good over two decades. Don’t forget that Graham did not mechanically purchase all NCAV shares. He also examined for business prospects, stability and quality of management. Here we are on shaky ground with FC because we really do not know, we can only think probabilistically. But then with this investment category we are not doing a Warren & Charlie ‘Inevitable’ analysis in which we expect excellent management, economic franchise with a deep and dangerous moat and fantastic stability in every case (Warren might say we are picking up cigar butts though). We have to be prepared to take a chance on an individual share when it forms part of an outperforming portfolio. In the Benjamin Graham paper we did not manage to include an analysis of the proportion of shares that individually underperform within a high performing portfolio. However, in another paper examining return reversal we found that that only 47% of our ‘loser’ firms earn positive market-adjusted returns during the five years following portfolio formation. On average, 7% of losers are liquidated during the five test period years, leaving 46% that survive but under-perform the market. Despite this the loser portfolio outperformed the market by 8.9% per year on average – a minority of firms with very good returns dominate the performance (‘Financial statement analysis and the return reversal effect’ Working paper ) Graham thought that high NCAV firms might turnaround because of one of the following: (1) Earning power would be lifted to the point where it was commensurate with the company’s asset level. This could come about in two ways (a) a general improvement in the industry – entry and exit dynamics mean that low industry profitability is frequently not as persistent as many market pessimists believe , (b) a change in the company’s operating policies – management running a company with such a low stock price relative to assets either respond voluntarily to take corrective action or they (or their replacements) are forced to by stockholders, such as adopting more efficient methods or abandonment of unprofitable lines. (1) A sale or merger with another corporation that could employ the firm’s assets would take place. It would pay at least the liquidation value. (2) Complete or partial liquidation could release value. The management of a corporation selling at below liquidation value need to provide a frank justification for continuing to operate. In the case of FC I cannot see clearly the most likely reviving factor. I can say that exit from the industry by rivals is very unlikely to be valuable because there is also so much industry entry to keep pressure up. Liquidation will not release value because everything will be taken by the landlords. The main hope is a change in the quality of management. Are they now properly awake? Is the new talent really good? We will not know for some time – we can only play the odds. Please keeping put up evidence that might help us assess the quality of management. I hope this helps Glen

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archive

I wrote newsletters for almost 10 years (2014 - 23) for publication on ADVFN. Here you can find old newsletters in full. I discussed investment decisions, basics of value investing and the strategies of legendary investors. Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed