|

How do you fancy a company which has about £34m of cash but is selling for £19m. Quite tempting? But you would also need to look at the total liability position relative to the easily realisable assets to be reassured that the cash is not needed to pay off debts. So, ignoring cash, what is the net current asset value, ‘NCAV-excluding-cash’. I get a figure of positive £12.4m. Thus all liabilities are more than covered by marketable assets, and then you get the cash on top. But, this is not enough for a decision. You also need to know if the management are pursuing a crazy course and throwing away the cash. Are they rapidly dissipating the cash surplus by persisting with loss-making operations or by making speculative capital investments, so that shareholders’ money will shortly be gone? I spent a long time trying to answer these questions – hence the delay since my last post, sorry – but I think I have reached a reasoned conclusion. Warning: risk of loss

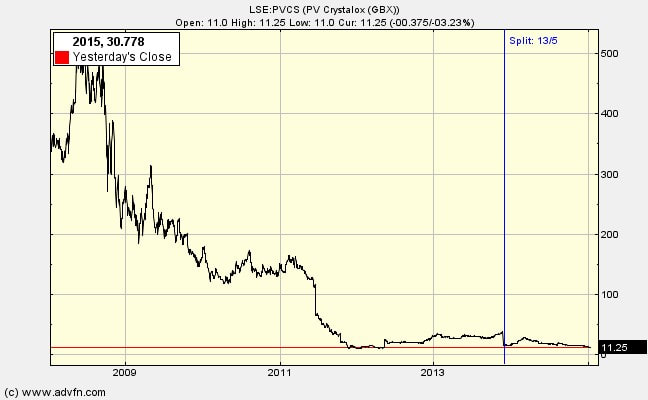

Be aware that this investment in my view has a more than 50% chance of being a loser. Should that automatically exclude it from a portfolio? No. If the payoff is 3 or 4 times money put in then even with a failure probability of 60% I will still invest. I tell myself to avoid narrow framing; think of the overall portfolio returns, not narrow sections of it. The business Back in the 1980s the company’s boffins/founders developed “multicrystalline silicon technology on an industrial scale, setting the industry standard for ingot production”. Let me explain. It sells its product to the photovoltaic solar cell industry worldwide, which as you know needs silicon. But not just any old silicon; it has to be from large crystals (PVC grows them up to 66cm). To make crystals it buys in something called “polysilicon”. After it has done its thing (I hope I’m not being too technical for you!) it has ‘ingots’ of ‘multicrystalline silicon’. It does not sell these lumps, but slices them into wafers and sells these to customers. This is where it does these things: Abingdon, UK: Ingots are produced. It has four production plants but two are mothballed (you’ll understand why later). High purity polysilicon under carefully controlled conditions is directionally solidified to multicrystalline silicon ingots. Erfurt, Germany: Wafers sliced from blocks Tokyo: Japanese subcontractors section ingots into blocks and wafers. Rollercoaster As you know, the demand for PV electricity production has rocketed in the last decade, with output of wafers rising in double percentage figures year after year. So PV Crystalox, PVC, has been able to charge high prices and make bumper profits year after year, right? Well it started that way. Until 2010 things were hunky-dory. Then the reality of no barriers-to-entry for the industry struck home. This industry story illustrates an important general lesson: you can have fast growth in customer demand together with losses - just ask the airline companies around the world, or TV manufacturers, or PC manufacturers, or…… The Chinese and others threw massive resources at solar power, including wafer makers. The result was oversupply, large annual losses and the scything of companies. PVC shares were priced at over £5 in 2008. They are now 12.1p. Such a decline would indicate that the generality of investors think they are going to keep-on selling wafers at a loss, and sooner or later go bust. Perhaps it will. But I think there is good reason for hope. I’ll start with a look at the balance sheet in tomorrow's post

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archive

I wrote newsletters for almost 10 years (2014 - 23) for publication on ADVFN. Here you can find old newsletters in full. I discussed investment decisions, basics of value investing and the strategies of legendary investors. Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed