|

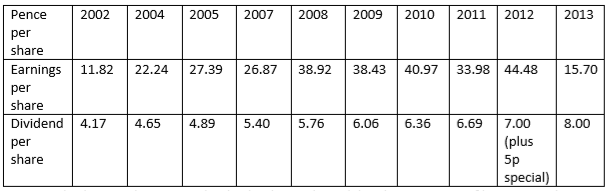

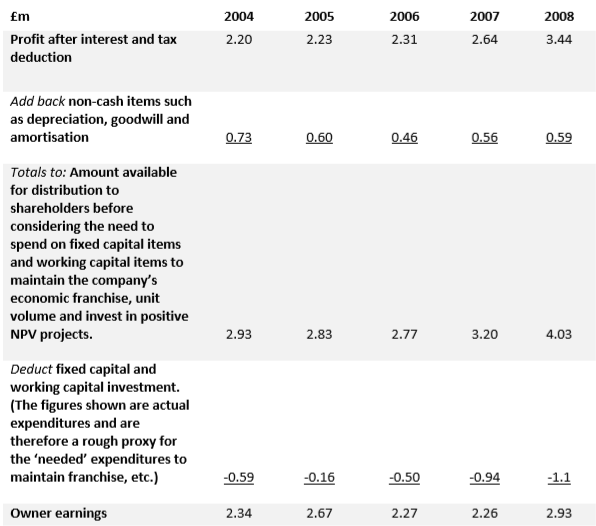

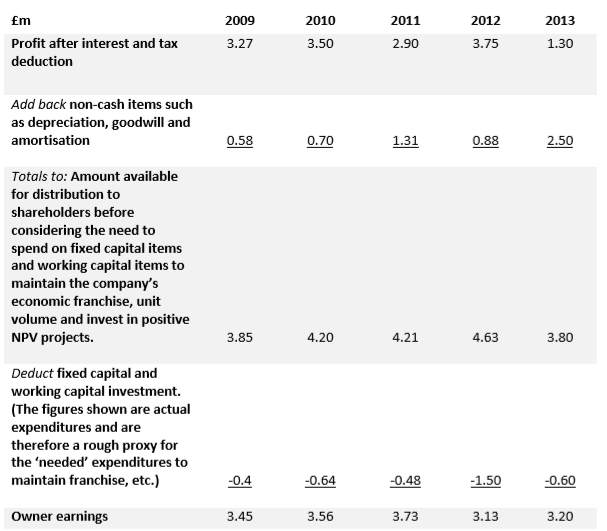

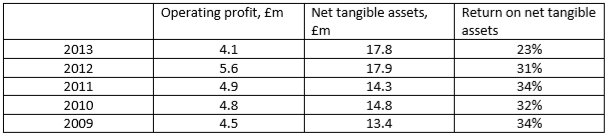

Dewhurst is a stalwart manufacturing company run by the same family for a century. It designs and manufactures components for lifts, ATM and other keypads and for trains. The two brothers currently in charge have decades of experience in this field and are supported by a stable professional team. They have grown profits both by organic means with an almost obsessive interest in design prowess and manufacturing efficiency, and by a measured acquisition strategy of companies supplying (generally) complementary products. Often these acquirees have had a long association with Dewhurst as suppliers or customers. Dewhurst are niche engineers, leaders in a number of small fields. For example, they control 90% of the UK market for lift components. The family has stuck to its knitting. Demand for individual product lines can be somewhat volatile from year to year, but because they apply their core knowledge and other strengths to selling into three distinct markets (lifts, trains, keypads for ATMs petrol pumps and ticket machines) and do so all over the world, the various ups and downs generally even out to produce a history of remarkably steady progress. They display resilience through economic vissitudes. There are 3.3m Ordinary shares carry voting rights and 5.2m Non-voting ‘A’ shares. Thus any overall earnings or valuation figure should be divided by 8.5m shares to derive per-share numbers. The Ordinary shares and the ‘A’ non-voting ordinary shares rank equally in all respects pari passu except that the ‘A’ non-voting ordinary shares do not carry the right to receive notices, attend or vote at meetings of the company. Until September 2012 the ‘A’ and the Ordinary shares were priced in the secondary market very close to each other. Then something strange happened given that the economic rights are equal – the voting shares rose a great deal more than the non-voting. Thus today the voting shares trade at £5.20 whereas the ‘A’ shares trade at £3.20. Market capitalisation: 3.3m Ordinary shares x £5.20 = £17.16m 5.2m Non-voting ‘A’ shares x £3.20 = £16.64m £33.80m Revenue split (2013) Lifts £34m Transport £3m Keypads £10m Conventional earnings per shares and dividends per share analysis. In 31 out of the last 32 years the dividend has grown by 5% or more. Estimated value per share using the dividend growth model and assuming an 8% pa required return with 5% pa future growth in dividend: Price = 8p ÷ (0.08 – 0.05) = 267p Note the very large dividend cover ratio. This might indicate that dividend could be raised significantly if the company does not have good internal projects to invest into. Price-earnings ratio for ‘A’ shares using average eps for 5 years: 320p ÷ 34.71p = 9.2 Owner earnings analysis To estimate intrinsic value we could take a rough average of recent owner earnings numbers and assume either (a) that this will continue year after year with no growth, or (b) less conservatively, that the annual owner earnings number will grow by, say, 5% per year. Let us take £3.3m as the proven annual earnings power. (a) Assume no growth and a required rate of return on equity of this risk class at 8% per annum: Intrinsic value = £3.3m ÷ 0.08 = £41.25m The company has 8.5 million shares in issue therefore the value of each share (ignoring the premium for voting rights) is £41.25m ÷ 8.5m = £4.85. (b) Assume owner earnings growth of 5% pa. Intrinsic value = £3.3m ÷ (0.08 – 0.05) = £110m On a per share basis: £110m ÷ 8.5m = £12.94 Return on tangible assets employed With the company displaying a long history of high retaining earnings (low dividend payout ratio) put to good use in acquisitions and organic growth, generating returns on tangible assets of over 30%, there should be significant future growth in owner earnings to look forward to if this performance continues.

Balance sheet strength Net asset value in total; £21.87m Net asset value per ‘A’ non-voting share: £2.57 Net tangible asset value in total: £17.86m Net tangible asset value per ‘A’ non-voting share: £2.10 Borrowing: zero Cash: £10.5m Pension deficit: £10.5m Character of the managers They have stuck to engineering, and with the exception of the mistake of the traffic management business (road bollards), they have focused exclusively on those areas where they have competitive advantage: lift components, keypads, train buttons, etc. However, they are now moving a little further away from the core by going for lift car manufacture and escalator belts. These moves are measured (£1m to £2m purchases every one or two years) and they are still reasonably well related to the core. They tell it like it is. No embellishment, frequently subsequent events show them to have been overly pessimista. Smart in assessing value in forms other than in engineering. For example, they recognised that the value of the factory in Hounslow would be worth considerably more if they obtained planning permission to build houses and then sold the land. It was sold for £6m in cash (£5m plus £1m of VAT) and then they paid a special dividend. The family own over 50% of the voting shares and have consistently demonstrated that they run the business as ‘if they are the sole asset of their families and will remain so for the next century’ (Buffett 1999), with steady growth within their circle of competence, constant bearing down on costs, high quality interaction with long-term customers, conservative investment and borrowing policies. Bulletin Board comments on the character of the managers are overwhelmingly positive. They are highly respected with long track record of treating shareholders well. They have carefully nurtured a family business in which they take great pride. Richard Dewhurst (Chairman) has an engineering degree and an accounting qualification. He has worked at Ford and as a management consultant. David Dewhurst, MD, has an engineering degree and previously worked at a brand design consultancy. Total director emoluments in 2013 were £654,000, with the highest paid director receiving £189,000. Richard Dewhurst bought 2,000 Non-voters in October 2013 at £2.849 Industry analysis (Asking if this industry is likely to achieve high rates of return on capital employed) It is very difficult to obtain information on these niche areas of engineering. In fact I could not find another push button manufacturer – this is more likely due to my unwillingness to search every international market rather than a complete absence of rivals. Much of what follows must be tentative given the poverty of solid data. -Threat of entry to the industry? The costs of entry are relatively low in terms of factory setup costs. However, the extant players have some name recognition and relationships with architects, building constructors and owners. However, in the face of a sustained onslaught from a new entrant offering lower prices this may be a relatively weak barrier. There is some degree of differentiation through design excellence but this is not a very strong barrier. Experience and knowledge of the industry may provide some protection, but it is not insuperable. -Rivalry in the industry? The high margins and return on assets indicate that the industry has settled down to a stable, gentlemanly way of pricing. The size of customer market is growing (more lifts in high-rise buildings, more trains, etc.) and therefore the stress of increased competitive pressure that comes from a decline industry is not a concern. -Substitute products? It is difficult to imagine potential substitutes being created to take away this industry. -Buyer power strength? There are a limited number of lift and train manufacturers in the world. However, these products are not commoditised because of the high design content. They are often specified by architects, e.g. push buttons in the Shard (Dewhurst’s specified). Also, they are not a large proportion of the cost of a lift/train/ATM installation and therefore the buyers may not push too hard on price. The consequences and risks of product failure are high, which also suggests that customers will pay up for quality (or perceived quality). Is it possible that lift/train/ATM manufacturers could integrate backwards and start manufacturing these components themselves thus limiting the prices charged as bought-in items? -Supplier power? Bought-in elements tend to be highly commoditised; many potential suppliers, thus little supplier power. -Industry evolution? Constant technological change is to be expected. This assists the existing highly experienced players so long as they continue to innovate (e.g. adopt touch screen technology – which Dewhurst is doing). Increased urbanisation and high-rise living and working are to be expected. There are 5 million lifts in Europe (278,000 in UK) half of which are more than 20 years old, therefore need replacement/updating to meet modern safety standards. China has 2.2 million lifts, N America 1.2 m and India 0.27 million. Accessibility for disabled is becoming increasingly important, thus more lifts will be needed both in public buildings and in homes. Extraordinary resources Dewhurst might possess, potentially lifting its return on capital employed above the industry average? -Tangible? None -Relationship? Mostly ordinary resources. However, they offer bespoke solutions to unusual requests from customers, architects, etc. There is a strong emphasis on service and quality. -Reputation? Mostly ordinary resources. However, it has been said that ‘Dewhurst’ are synonymous with lift components in the minds of many architects. -Attitude? A possible extraordinary resource. They appear incredibly focused on their niches with a determination to be the best. -Capabilities? The combinations of skills need to supply solutions for clients may amount to an extraordinary resource. This may be based on path dependency, i.e. the route they took, over a century, to get to where they are today, building up skills within the team (and name recognition over decades) may have created competitive advantages. -Knowledge? A possible extraordinary resource. The implicit knowledge of customers, design and technology built over time may allow superior returns relative to less knowledgeable competitors. Are these possible extraordinary resources demanded, scarce and appropriable? -Demanded? Yes, customers do need these technical, design, service and efficiency qualities. They need good relationships with a supplier of specialised components. They need superior capabilities and knowledge of these niche products. -Scarce? I cannot find alternative suppliers. That is my failing I suspect, rather than an absence of strong competitors. However the returns on assets over the past five years indicates that there is not an abundance of similar companies that customers can turn to. -Appropriable? Will the value created by the firm’s output accrue to Dewhurst or be appropriated by employees, suppliers, customers or others? The suppliers of inputs, including employees, seem to have little bargaining strength and so are unlikely to appropriate a high proportion of the value (e.g. no ‘star’ employees on large bonuses). Customers have greater bargaining strength, but Dewhurst’s history of high return on assets indicates that Dewhurst appropriates a great deal of the value they create as well as creating large consumer surplus for customers. Can Dewhurst resources be leveraged? Yes. They are already applying their reputation, contacts, knowledge of continuous improvement in manufacturing, knowledge of customer requirements to the new businesses they acquire in closely-related niches. They can continue to employ these competitive strengths to additional acquisitions. The directors point to synergies in product development carried out in London having an impact on operations in America, Australasia and Asia. Some questions 1. The large decrease in reported profit for 2013 is a concern. Is it a one-off or will the company continue to suffer? Note that operating profit declined by a more modest 27% and revenue by 15%. The largest contributors to the reported profit decline were a goodwill write-off and a return to more normal keypad sales. 2. Will one of the giant engineer companies invade their markets? 3. Will they acquire more companies beyond their circle of competence or that are in industries with poor economic characteristics, as they did with Traffic Management Products? 4. There are a small number of lift manufacturers. Could they gang-up to oppress suppliers such as Dewhurst? They have a history of getting into trouble with the antitrust authorities, e.g. fined €1bn by EC for illegal price agreements in 2000. In 2014 Spain fined four lift companies for trying to keep rivals out of maintenance market. 5. I have not done enough digging yet to be fully confident in my industry analysis and competitive resource analysis. What have I missed? Who are their competitors?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archive

I wrote newsletters for almost 10 years (2014 - 23) for publication on ADVFN. Here you can find old newsletters in full. I discussed investment decisions, basics of value investing and the strategies of legendary investors. Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed